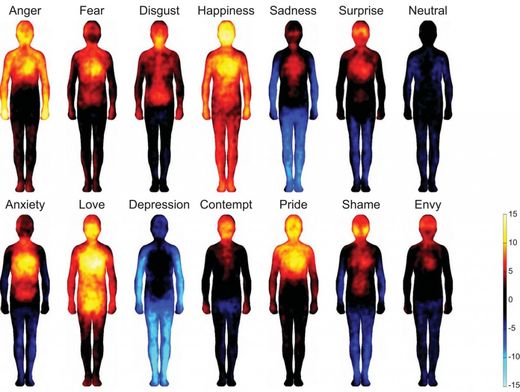

Yellow shows regions of increased sensation while blue areas represent decreased feeling in these composite images

Researchers have long known that emotions are connected to a range of physiological changes, from nervous job candidates' sweaty palms to the racing pulse that results from hearing a strange noise at night. But new research reveals that emotional states are universally associated with certain bodily sensations, regardless of individuals' culture or language.

Once More With Feeling

More than 700 participants in Finland, Sweden and Taiwan participated in experiments aimed at mapping their bodily sensations in connection with specific emotions. Participants viewed emotion-laden words, videos, facial expressions and stories. They then self-reported areas of their bodies that felt different than before they'd viewed the material. By coloring in two computer-generated silhouettes - one to note areas of increased bodily sensation and the second to mark areas of decreased sensation - participants were able to provide researchers with a broad base of data showing both positive and negative bodily responses to different emotions.

Researchers found statistically discrete areas for each emotion tested, such as happiness, contempt and love, that were consistent regardless of respondents' nationality. Afterward, researchers applied controls to reduce the risk that participants may have been biased by sensation-specific phrases common to many languages (such as the English "cold feet" as a metaphor for fear, reluctance or hesitation). The results are published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Hot-Headed

Although each emotion produced a specific map of bodily sensation, researchers did identify some areas of overlap. Basic emotions, such as anger and fear, caused an increase in sensation in the upper chest area, likely corresponding to increases in pulse and respiration rate. Happiness was the only emotion tested that increased sensation all over the body.

The findings enhance researchers' understanding of how we process emotions. Despite differences in culture and language, it appears our physical experience of feelings is remarkably consistent across different populations. The researchers believe that further development of these bodily sensation maps may one day result in a new way of identifying and treating emotional disorders.